Q: Even after 75 years of independence, India is home to one in every three illiterate adults in the world. India currently has nearly 30 crore illiterates. What is the root cause of the failure in the education sector?

A: If there is a root cause, personally I think it is the indifference of the privileged classes towards the education of poor children, and especially of Dalit and Adivasi kids. This year itself we have seen dramatic examples of this indifference. For instance, not many of your viewers may know that the school education budget was slashed by 10% this year, even though the overall budget of the Central government shot up by almost 20%. This is a drastic cut, but it went unnoticed when it happened last February. In fact, there was no discussion about this. It clearly reflects the low importance given to primary education. Similarly, the education sector is going through a deep crisis. Students have been shut out of schools for almost two years, and now, they are unprepared to go back to school and resume their learning activities. This transition requires a lot of preparation and thought and resources, but none of this is happening in significant measure. It shows how the country and privileged classes are turning a blind eye to the education of the needy.

Q: Nearly 40% of our children go to private schools at primary level, when compared to below 10% in many developed nations. What kind of implications do you see because of this..!?

A: That's true. I think the Indian public is not well aware of some of these facts. In most of the developed countries, it is the norm for most children to go to government schools, or sometimes to private non-profit schools. Not only in developed countries, but in most other countries as well. However, in India and a few other countries, things are quite different. In India, more than one-third of students at the primary level go to private schools (read profit-making schools), and the count is growing by the day. On top of this, there is a lot of stratification within the private system, with standards in low-fee private schools being as bad or worse than in government schools, and expensive private schools being on par with the best schools in the world. Even among government schools, there are many disparities. Students studying in schools situated in unprivileged areas are suffering due to dysfunctional schools, whereas Navodaya Vidyalayas are maintaining good standards. So there are multiple layers of stratification in the education system, which reinforce economic and social inequalities. Universal quality education could make a major contribution to greater equity in Indian society. But today's schooling system does not serve that purpose at all.

Q: As you said, inequalities in education is leading to social inequalities. How to address this problem!?

A: It is a big challenge because the schooling system has been ruined. It will take a kind of national movement to set things right and ensure quality education for all children. When the political leadership throws its weight behind something, it often starts moving. We have seen this in the sanitation campaign, PDS reforms and the vaccination programme. If a similar commitment were shown to elementary education over a period of time, we could make progress. Because a lot of research has been done in recent years on how to improve the schooling system, so there are ideas around. For instance, we know that one major problem in the government schooling system in India is that some students in the same class are unable to keep up with others. To address this inequality within the classroom, we need better pre-school education in Anganwadi's, and budgets have to be provided for the same. We also need to place more power in the hands of parents, who are now better educated than in the past. Parents have an idea of what is happening in schools and have higher expectations than before. But when a dysfunctional school denies their aspirations, they are helpless. So we need to involve them more actively in the system. But first, we need to discard the rampant lack of seriousness in the schooling system.

Q: As per UNESCO reports, India has nearly 11 lakh schools with single teachers…

A: That's right, and then also there are also many schools run by para-teachers. In Jharkhand, where I live, the teachers in entire blocks are supposed to be supervised or supported by so-called block resource persons who are contract employees with lower qualifications and salaries than the teachers themselves. That cannot work. There are many aberrations in the schooling system that can be fixed. Even the basic facilities for that matter. But for all this to change, we need to give the schooling system more attention and resources.

Q: Early this year, you conducted a survey of 1400 underprivileged children and their families across the country with student volunteers, what were the main findings of the survey?

A: One of the main findings was that online education is fiction for poor children. We found that in rural areas, among underprivileged families, only 8% of children were studying online regularly. This is important to say, even if it is obvious to some of your viewers because the central government has created an impression that online education saved the day during the Covid-19 crisis. That may be true for a small minority of privileged children, mainly in urban areas, but it is not true for the vast majority of poor children. The reason why so many children are unable to study online is not just that they may be deprived of a smartphone, there are other reasons like not having money to recharge, poor network connectivity, and lack of an appropriate study atmosphere at home. Also, many are unable to understand the online material sent by the schools.

The flip side of this is that half of the offline children in rural areas were not studying at all at the time of the survey. They were just roaming around, playing with their friends and so on. The third important finding was that many of these children were unable to recall what they had learnt. We conducted a very simple reading test as part of this survey and asked children to read a simple sentence. In rural areas, among those enrolled in Class 3, only 25 per cent could read that sentence. This is much worse than any of the baseline surveys that are available.

So now the situation is that these children have forgotten what they've learnt, but they are being promoted two years ahead of the grade they were enrolled in before the Covid crisis. That creates an urgent need for radical provisions to make it possible for these children to continue studying and not become de facto dropouts.

Q: What kind of changes do you suggest for schools in terms of curriculum and pedagogy to deal with the present crisis?

A: The most important thing is to wake up to the gravity of the situation and avoid shortcuts. We have to realize the glaring gap that separates poor children from the curriculum of the grade in which they are enrolled, and we should have no illusion that this can be dealt with by short-term bridge courses.

Many states are basically trying to get back to business as usual in a hurry, this is a recipe for disaster. Either the curriculum needs to be drastically simplified, or the children have to be given more time, or they have to be given serious additional support through bridge courses or other means over an extended period of time. Of course, we can do a little bit of all three. But we cannot keep the curriculum and pedagogy more or less as they are, with a short-term bridge course thrown in, and hope that these children are going to be able to cope.

A few days ago I had a discussion with a teacher in a primary school in Chhattisgarh, and asked about children forgetting what they have learnt, she said, "I cannot do anything for these children because I cannot slow down the entire class for them". That is exactly the kind of attitude i think they have to avoid. We have to give priority to these children, instead of writing them off.

Q: Government has set a 5 trillion USD economy target to be achieved by 2025. Is it possible amid poor performance in education? Are education and economic development not connected!?

A: Of course, they are connected. First of all, I think this goal of India becoming a five trillion dollar economy by 2025 is best ignored, because there is no plausible scenario where this could be achieved. Secondly, I think we need to focus not on economic growth but on overall development. Development does not mean having more US Dollars, but people living well with good nourishment, education, longer life, more freedom and so on. Of course, if the economy is growing well it can help, but only if the resources are used to improve the lives of poor people. So we have to focus on development and not growth per se. And if we think about development, then yes, education is most important. It's important for growth, health, social equity and also for democracy. I think this is one of the most solid connections that have emerged from development economics in the last 20 years. This is another reason for giving more importance to education, and especially to elementary education than the country is giving at the moment.

Q: Which are the countries moving in the right direction in education among the developing countries! What can we learn from them?

A: I think we can learn from many countries. Most countries in Asia outside South Asia have given a lot of importance to education and made big investments in schooling at an early stage of development, and reaped rich benefits from it.

Even within South Asia, we can learn from Sri Lanka, which is far ahead of India in elementary education. Incidentally, most schools in Sri Lanka are government schools. In fact, private schools were nationalised a few decades ago. Most children study in government or government-aided schools. I am not saying that India can follow suit. But we can draw inspiration from this radical step based on recognizing the cardinal importance of elementary education for development.

And by the way, we can also learn from some Indian states that have given a big push to elementary education, for instance, Kerala, much before Independence, Tamil Nadu, very soon after Independence, and Himachal Pradesh, soon after it became an independent state in the early 1970s. At that time, Himachal was considered a backward region, so much so that there were doubts whether it would even survive as an independent state. Years later, literacy rates were on par with Kerala in the younger age groups, again enabling Himachal to make rapid progress in many fields.

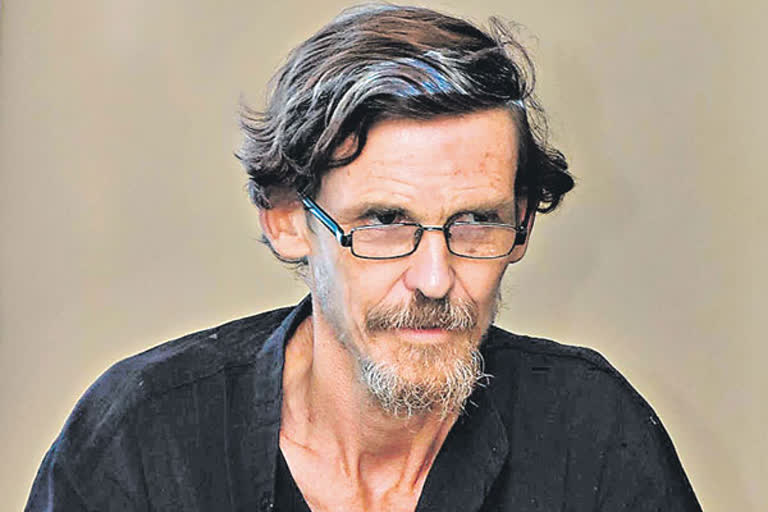

Also read: EXCLUSIVE: Center must take responsibility in helping migrant workers, says Jean Dreze